You meet up with six friends for dinner and drinks. You didn’t make a plan so you start wandering around an area with a lot of restaurants with the goal of picking somewhere to eat. You stop to look at menus as you go but nothing seems to be getting agreement: one friend doesn’t fancy Chinese food, another isn’t keen on Italian, no one really says anything as you stand outside the curry house. Time ticks on. You walk and walk, getting hungrier and hungrier. Eventually someone snaps and you end up traipsing into the restaurant you happen to be standing by. No one is happy but somehow this is what always happens when you decide as a group.

This situation - a suboptimal choice when confronted with many options - happens all the time: businesses try and do everything because they can’t agree what the focus should be (“everything is important” = nothing gets prioritised sufficiently); people find themselves miserable in their job because they have optimised for the wrong thing (a bigger salary, perhaps, or more responsibility) without examining which things are actually most important to them (having time for the gym, or being intellectually stimulated, perhaps); politicians make so many promises that they can’t keep any; and we even find ourselves failing to meet the needs of those we love because we haven’t properly understood what it is that they value most from us.

There are many reasons this happens but often it is simply because we haven’t taken the time to explicitly understand the preferences of those involved in a decision. In these cases, a fifteen minute pairwise comparison activity can have an enormous return.

So… what is pairwise comparison?

The easiest way to explain pairwise comparison is using the children’s game “Would you Rather?”. In “Would you Rather?” you are presented with two options and asked to choose between them. They are often disgusting or silly and coming up with the pairs is most of the fun. For example, “would you rather eat a slice of bread that has been in your shoe or your armpit?”. Pairwise comparison allows you to make a longer list of options and then compare them in pairs that are selected at random. By doing this multiple times over you can elicit a a hierarchy of preference among the options as well as understanding how strong those preferences are. The graph below shows how this might work by giving the results of a game of “Would you Rather?” using pairwise comparison. I created this game using the All Our Ideas website. 63 people “played”, casting 1,265 votes overall:

Now, imagine for a second that these 63 people were actually going to have to do one of these disgusting activities. Between them they have to agree which of the options they will choose. Unstructured, conversations like this are usually a disaster. If they were given an hour to come to an agreement they would spend the first half hour talking about how much they didn’t want to give up brushing their teeth, an option that no one is going to choose. Someone in the group would feel extremely strongly about toilet-related activities and would take up valuable time imploring the others not to choose those. People would start talking about how cockroaches are routinely eaten in some cultures… and so on and so on. At the end, having barely discussed the top options, the group would be lucky to land on the collective preference of eating the armpit bread.

But if they did this exercise and were presented with this data then they could focus the discussion effectively. They could explore whether anyone had a strong aversion to the top option - armpit bread - over all others. And, if it turned out they did, whether the group would be willing to compromise and move to shoe bread instead.

Real life is full of “Would you Rather?” style questions where the goal is to land on one preferred option (or to figure out how to allocate resource across a set of options) from a long list. Questions like: “which feature is most important for this product?”, “where should we go on holiday?”, “who should get a pay rise?”, “if a government has to make cuts, should it be to healthcare or benefits?”, or “what should we call our child?”.

Whipping out the pairwise comparison software may not always seem appropriate but it will often lead to far better decisions!

With that, I will leave you with some of my favourite (trivial) surveys I have run using All Our Ideas.

Which Love Actually Storyline is the best? (a good example of how the crowd can be completely wrong - obviously it’s Hugh Grant phoning in his job as the Prime Minister)

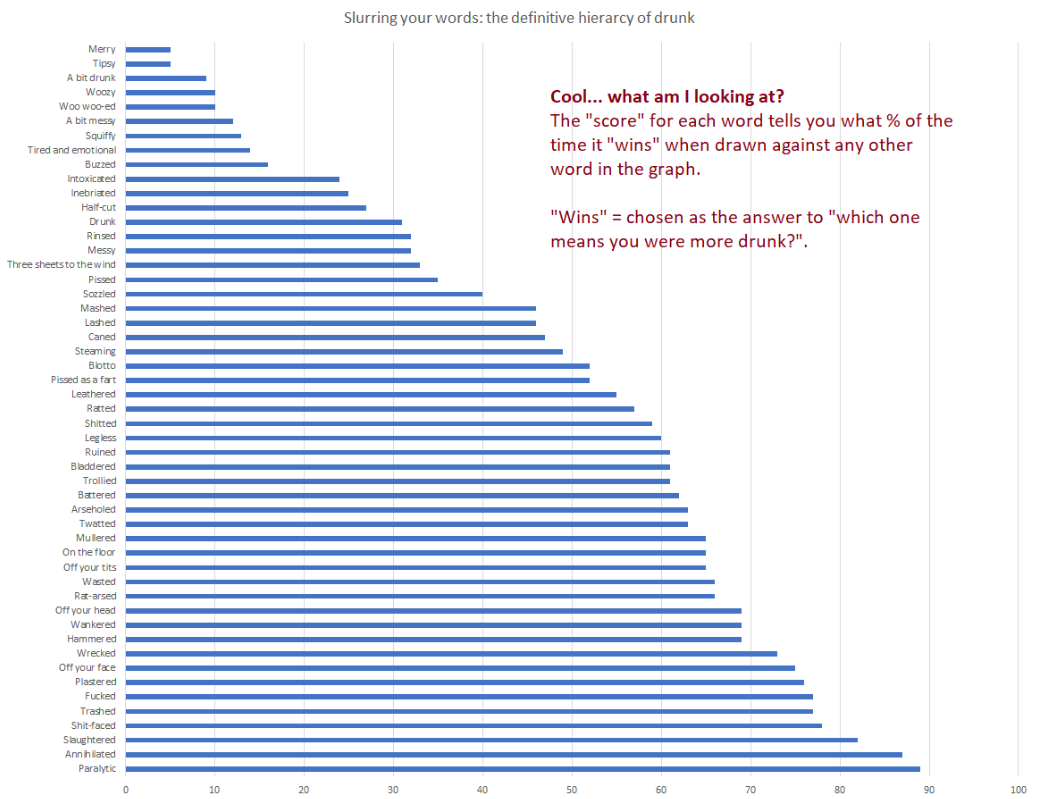

What is the hierarchy of drunkeness among the english language’s synonyms for inebriation?

1. Swears = more drunk. Average score for an adjective containing a swear is 62.6 vs 46.05 without.

2. Body parts = more drunk. Average score if the adjective includes a body part is 67.86 vs 46.34 without.

3. There’s a hierarchy of body parts. Implicating that face happens once things have got out of hand (“shit-faced” = 77). To be “off your…” “face” (75), “head” (69), and “tits” (65) mean different things.

4. At a glance, there seem to be ~5 clusters of similarly scored adjectives, as though being drunk happens in five steps. 5. The top three (paralytic, annihilated, slaughtered) don’t contain swears or body parts but they od imply grave physical danger.

What’s the worst swear? Female genital words top the list, then sex words. Wombles and weasels make words worse. And “nob” is less offensive than “dick”.